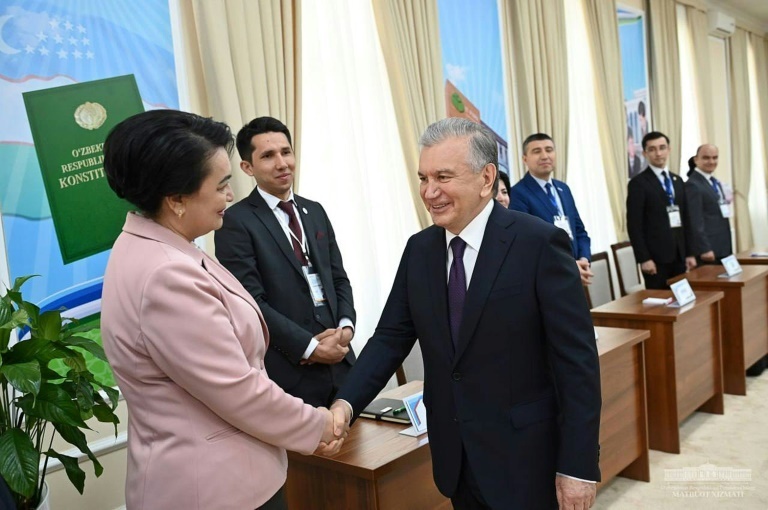

Uzbekistan's President Shavkat Mirziyoyev is credited with leading Central Asia's most populous country out of isolation, but his appetite for change may be waning now that he has consolidated power.

His country has just voted for constitutional changes allowing him to stay in office until 2040, in an election observers said lacked pluralism and competition.

Mirziyoyev's reforms -- including ending infamous forced labour in the cotton industry -- have been hailed both by long-suffering citizens and foreign observers.

The bar was set low by his hardline mentor and predecessor Islam Karimov, who gained a reputation for torturing opponents including by boiling and freezing them.

Mirziyoyev, born in 1957 in the east of Soviet Uzbekistan, served in Karimov's government for 13 years.

When Karimov died in 2016 after ruling for more than a quarter of a century, Mirziyoyev's role as heir quickly became clear.

He took control of Karimov's funeral arrangements and outmanoeuvred the head of Uzbekistan's notorious security service, Rustam Inoyatov, to become leader.

He launched changes unthinkable under his predecessor, but his critics say some recent moves carry echoes of the country's despotic past.

- Out of isolation -

The grey-haired 65-year-old opened up the country's economy and trade, as well tourism and foreign investment.

Ties with neighbouring Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan -- countries Karimov once threatened with war over hydropower projects -- have improved.

Mirziyoyev has advocated pragmatic ties with the Taliban in neighbouring Afghanistan, while trade with Russia and China has grown -- although he has stopped short of rejoining a Moscow-led security bloc.

Mirziyoyev's most celebrated achievement has been his clampdown on forced labour in the cotton fields, where wages for up to two million pickers have increased year-on-year.

Authorities hope Western firms will now end a long-standing boycott after the International Labour Organisation heralded the end of systemic child labour and forced labour.

Mirziyoyev once boasted that under his leadership, Uzbeks had learned to "live free, without fear".

But his critics say there is more continuity than change, suggesting Mirziyoyev might not be the man to totally overhaul Uzbekistan's reputation as a rights abuser.

- Bloody protests -

Less than a year into Mirziyoyev's second term, protests broke out in the country's Karakalpakstan area in July 2022 over a move to remove the region's right to self-determination.

The unrest left at least 21 dead and forced Mirziyoyev to make a rare about-turn and walk back the proposed changes.

Human Rights Watch said in November that the authorities "unjustifiably used lethal force... to disperse mainly peaceful demonstrators" after verifying dozens of videos and photos of the protests.

Human Rights Watch said that "a trial of some of the protesters opened... but there remained a lack of accountability for the 21 people killed and dozens who were seriously wounded."

Mirziyoyev is also facing accusations of nepotism.

The public prominence of the eldest of his two daughters, Saida Mirziyoyeva, 36, who held a post in the state communications agency until last year, has drawn comparisons with Karimov's eldest daughter, Gulnara Karimova.

Karimova, referred to as a "robber baron" in leaked US diplomatic cables, is currently jailed on embezzlement and criminal conspiracy charges after falling foul of her father's regime while he was still alive.

bur/giv

© Agence France-Presse

Your content is great. However, if any of the content contained herein violates any rights of yours, including those of copyright, please contact us immediately by e-mail at media[@]kissrpr.com.

Source: Story.KISSPR.com