It's not yet dawn but dozens of troops from Niger and France's legendary Foreign Legion are boarding a French C-130 military transport plane, each weighed down with gear.

In the green-lit hold, their faces are locked in concentration as the aircraft takes off over the arid Sahel. A few soldiers manage to doze off, their heads resting on their bags or their heavy helmets.

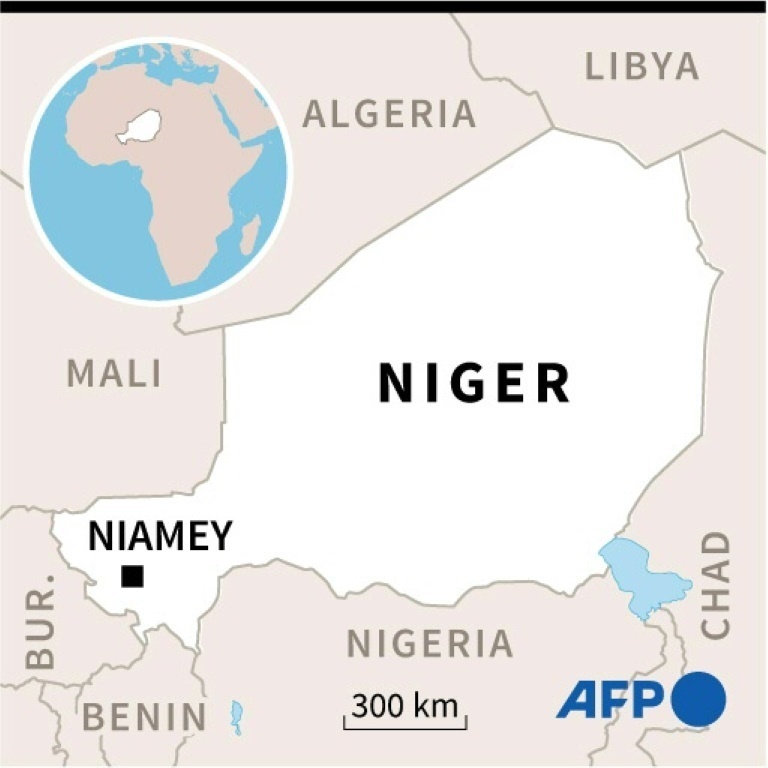

Their mission: to make a parachute jump to take an abandoned military position in Niger not far from the Malian border -- an area where the ruthless Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (IS-GS) is resurgent.

The joint operation is symbolic of the new approach President Emmanuel Macron wants to use for France's mission in West Africa's deeply troubled Sahel.

After nearly a decade, its troops were forced to pull out of Mali -- still fighting an Islamist insurgency -- following a military coup.

The junta then, according to Western governments, called on Russia's Wagner mercenary group for help.

France's exit from Mali has encouraged the jihadists to regain freedom of movement in the border region -- and the parachute operation is aimed at keeping them at bay.

The alarm rings. The aircraft's side doors open. Time to jump.

"Don't stop!" shouts an officer as the paratroopers hurl themselves into the night at a frantic pace, filling the sky with mushrooms of beige silk.

On the ground, the soldiers are about to get to work.

- 'Laboratory' -

The cooperation with Niger is part of a strategy which Paris hopes will show the key lesson from Mali: support local forces by providing the equipment and expertise they need, but don't substitute for them.

"In Niger and everywhere in Africa, the idea is now different from what was done in Mali. Today our help starts with what the partner needs," said the commander of the French forces in the Sahel, General Bruno Baratz.

The pullout last year from Mali brought the curtain down on the long-running Barkhane operation against Islamist militants in the francophone ex-colonial region -- a hugely problematic deployment that left over 50 French troops dead.

Neighbouring Burkina Faso, also led by a junta, this year also pushed out French forces from its territory, a prelude to what the West fears will also be a pivot to Wagner.

The new strategy is upheld to the letter in Niger, which has accepted 1,500 French soldiers on its soil to bolster its armies at a time when IS-GS is once again a threat.

Ahead of the jump over Liptako, a commander with the Foreign Legion's 2nd Paratroop Regiment told the assembled troops that the mission would be "hard."

"There's heat, there's the environment, and we don't know where the enemy is. We are counting on you to help us," he said to the Nigerien troops.

"I believe the French army is trying to use Niger as a laboratory for new relationships" in Sahel, and "be a supporter rather than a leader" said Michael Shurkin, director of global programmes at risk management firm 14N Strategies.

"France is convinced it needs to be as discreet as possible," he said.

"France was fighting its own war in parallel to what Malians were doing. Now France is trying to do things differently."

- Niger strategy -

A French military officer, who asked not to be named, said the new strategy still meant a "de-Barkhane-isation" of attitudes in the French armed forces, who grew used to tracking militants in the desert in much more autonomous conditions.

But Niger seems satisfied.

In Mali, Barkhane notched up undeniable tactical victories against the jihadists.

But the country's political authorities never managed to re-establish control in areas purged of militants. And the Malian army remained fragile, despite years-long efforts to strengthen it.

Cooperation with Niamey, however, is smoother.

"Niger has a particularly effective counter-insurgency strategy," combining population security and the return to the state to disputed areas, Baratz said.

dab-sjw/tgb/ri

© Agence France-Presse

Your content is great. However, if any of the content contained herein violates any rights of yours, including those of copyright, please contact us immediately by e-mail at media[@]kissrpr.com.

Source: Story.KISSPR.com